MATT’S DOG BLOG

How to Train Your Dog to Accept a Muzzle

Muzzle conditioning, or muzzle training, is a valuable lesson that all dogs should have. Muzzles have an unfortunate stigma among humans. Too many people are resistant to muzzling their dogs. This is a shame. The ability to muzzle your dog should be no more controversial than the ability to put on a pair of glasses when you need them. The biggest difference is we can’t tell our dogs what this device is or why they have to wear it. This video shows my process for acclimating dogs to muzzles easily. It also discusses why your dog should be muzzle trained, regardless of their demeanor.

Why I Never Take My Dogs to Dog Parks, Daycares, or Allow On-Leash Greetings

Dog parks, daycares, and on-leash greetings are all incongruent with normal canine behavior. They can easily create behavioral issues or worsen existing ones. Even in playful, friendly dogs, they can create the unhealthy idea that our dogs are going to get to greet every other dog. Many other dogs become fearful, reactive, or even aggressive as a result of being forced into these uncomfortable situations. For this reason, I highly recommend that dog owners forgo all three.

Dog parks are unstructured social settings where it’s expected that dogs will run up to each other and play. But for most dogs, the sight of a strange dog running up to them is unsettling at best. Canine packs do not behave this way in the wild. And as a result, the number of fights that occur within dog parks is staggering. Dogs are hurt and killed in them daily. Even friendly dogs can get into fights when play styles and energy levels do not match. But let’s assume nothing catastrophic will happen: Going to dog parks regularly demonstrates to most dogs that their humans are not in control of their surroundings. This undermines trust and over time, this will weaken your bond and your ability to manage your dog’s behavior. Even for dogs who love the attention of others, it reinforces that other dogs exist to be played with, often making them the single greatest reinforcer to your dog. You can’t very well call your dog off a distraction if the distraction is more rewarding than you are.

Daycares have the advantage of having supervision and referees, at least in theory. Many will attempt to match dogs by size and energy levels. And they do a pretty good job of preventing fights, though they still happen. I have many clients whose dogs became aggressive after getting attacked at daycare. The biggest issue is that we cannot know with 100% certainty what behaviors are being reinforced when our dogs are there. Even well-intentioned and reputable daycares will do things that are counter to training you may be doing: They might be letting dogs charge through gates when they open, bark excitedly at each other and humans, or jump for attention. And like dog parks, they create unhealthy expectations of getting to greet other dogs. Depending on your work schedule, they may be necessary to at least break up your dog’s day. But if your budget allows it, an individual dog walker would be better.

On-leash greetings are a final issue that seem like they solve the problems of the first two. They involve only two dogs, instead of a group. You’re there holding the leash, so you can enforce rules that matter to you. But it becomes something that humans do because of a misunderstanding of what “socialization” is, not because the dogs actually need it. Second, two dogs will often be at least curious about each other, and therefore pull towards each other as you approach. The taut leashes generate frustration and often anxiety, which can explode into a fight. They can also tangle as the dogs move to sniff around each other, trapping them together before they are ready. Finally, the other owner is often a stranger, whose expectations of normal canine behavior may not match yours. When two dogs meet, it’s vitally important that their owners agree what behavior is and is not allowed, so that they may intervene appropriately. All this to say: reserve greetings for dogs you’re going to have to see regularly. Do them only with dogs whose owners you know well and share your expectations. Even then, understand that dogs do not have to be friends.

These three situations are the cause of so much frustration, confusion, and aggression in the dog community. They exist to meet our very human desire for our dogs to have friends, but fail to meet the evolutionary needs of the dogs. And to be clear, your dog absolutely can have friends. But forcing your dog into tense environments for the sake of making friends with total strangers is odd behavior with little to no benefit and huge potential consequences. If you are doing any kind of behavioral modification with your dog, they remain huge variables which will cause unpredictable results. And even if you have the “perfect dog” and things are going well, one bad experience is enough to create a problem. Anytime I am training someone’s dog, I make sure they are aware of the implications of continuing to do these three things. They are absolutely the three fastest ways to mess up your dog’s behavior and mindset.

Service Dogs

“Is the dog a service animal required because of a disability?”

“What work or task has the dog been trained to perform?”

Those are the two questions that you can be legally asked to confirm the legitimacy of your service dog.

People frequently contact me and ask if I can train their dog to be a service dog. But the real question should be:

“Can you help me train my dog to do (TASK) in order to help me with (DISABILITY)?”

Per the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), your service dog does not need to be certified by any organization. Your service dog does not need to wear an identifying vest. Your service dog does not even need to be professionally trained! Your service dog does need to be able to perform a specific task on your behalf - one that you can explain when asked. “She guides me safely in public,” is a task. “He alerts me of my blood sugar levels,” would also qualify. These are by no means the only appropriate answers. However, please note that these are concrete, definable jobs that mitigate the effects of a disability - not ambiguous titles which we assign to the dog.

Emotional support, comfort, companion, or therapy dogs are not considered service animals under the ADA and are not entitled to the same freedoms as service dogs.

Though professional training is not a requirement, you will also want to ensure that your service dog, if you need one, is well-behaved and fully housebroken, or it can be excluded from public places like any other dog. You must be able to control your service dog at all times, with or without a leash. The handler of a dog that is out of control can be legally ordered to leave a public space if they cannot control their dog.

In 2020 the US DOT implemented additional criteria unique to the airline industry. These include (but are not limited to):

The requirement to be leashed

Limiting a person to 2 service dogs in transit

Limiting the space a service dog may occupy in-flight

Specifically excluding emotional support dogs

Acknowledging the legitimacy of psychiatric service dogs (distinct from ESAs)

Requiring a DOT Service Animal Air Transportation Form attesting to the dog’s training and behavior

If you have a legitimate need for a service dog, I highly suggest hiring a trainer who specializes in training the type of task(s) you require.

Because nobody is required to professionally train their service animals, there is no certifying body, central authority, or directory of all available trainers of service dogs. However, Assistance Dogs International has a pretty extensive directory you can use as a starting point:

For more information on service animal laws, please follow up with these ADA and DOT sources:

Operant Conditioning

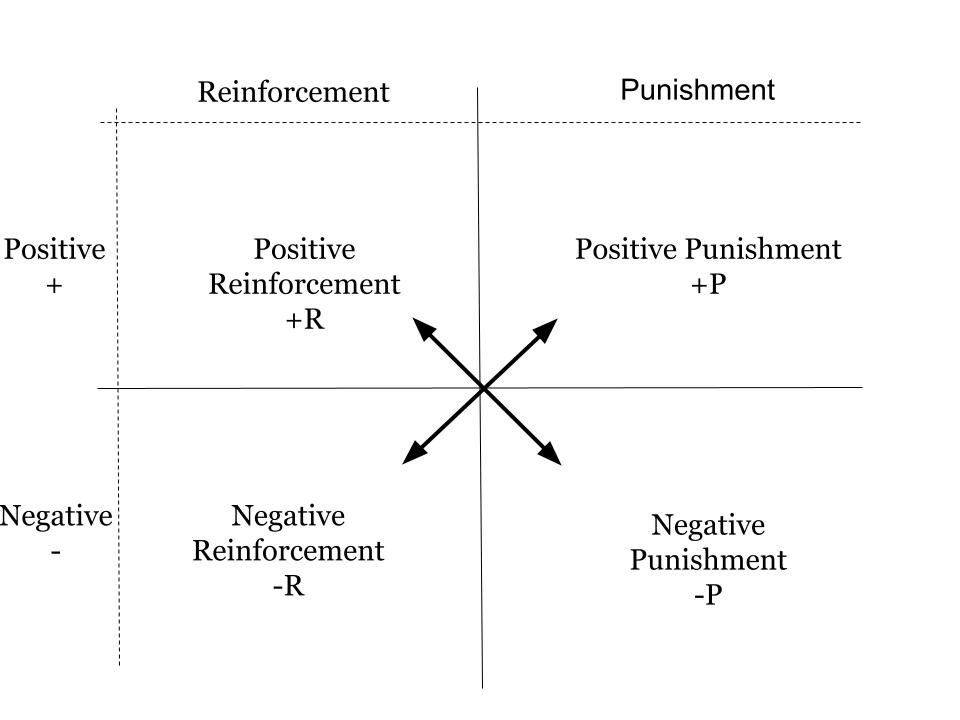

This form of learning requires input from dogs and is the primary way in which we can affect their behavior. Our dogs can generate a response through action or inaction. Operant conditioning consists of four methods of learning, categorized as either positive or negative and either reinforcement or punishment.

The terms positive and negative require some explanation. These terms do not refer to anything good or bad, pleasant or unpleasant. In this context, they are referring to either adding some stimulus or removing it. This giving and taking is the thing that you do in order to influence your dog’s behavior. Reinforcement and punishment are more self-explanatory. Reinforcement involves making the dog more likely to repeat a behavior, while punishment will make the dog less likely to repeat a behavior.

As you can see from the table above, you can give to reinforce or punish behavior. You can also take to reinforce or punish behavior. This concept is confusing for many, and admittedly the differences are sometimes subtle. Below are some examples of how these concepts work, in human terms:

Positive Reinforcement -

Do well on a test and your teacher gives you an A. Show up to work and do your job, you get paid. You are given something (positive) in order to encourage you to repeat (reinforce) a behavior, such as studying or working.

Positive Punishment -

A police officer pulls you over for speeding. Depending on the officer’s mood, your demeanor, and just how fast you were actually going, you may get a ticket. You have been given a fine (positive) in order to reduce the likelihood (punishment) of you speeding in the future.

Negative Reinforcement -

In the years following that speeding ticket or at-fault car accident, your insurance premiums will be higher because you are considered a higher risk to the insurance company. If you behave yourself long enough, those events drop off your record, and your premiums become less expensive. Your insurer lowers your prices (negative) to encourage you to keep driving safely (reinforcement).

Negative Punishment -

If you drive badly enough, the state will take away your license to drive (negative) in order to make you less likely to drive badly (punishment).

You may have noticed I was not able to provide a driving-related example of positive reinforcement. Why do you think that is? Imagine if it were possible for the state to know if you behaved yourself all month, drove the speed limit, stopped fully at every stop sign, and used your turn signal. If you were to receive $100 in your bank account for every month you did these things, would you? What if you got $1,000? $10,000? And what if there were no downside to speeding - no chance of getting caught? Or if you were caught, perhaps the fine was some trivial amount like $5, without the subsequent insurance hike. Would you speed then? Think about how this applies to your dog.

This is how all animals learn and change their behavior. There is no debate about this. It’s a settled issue. These concepts are biological truths, first introduced by Edward Thorndike at the turn of the 20th Century and then refined by B.F. Skinner in the 1930s. All four methods have their place in dog training. Look at these examples long enough, and you will realize there is no way to eliminate punishment from training. Negative punishment is the antithesis of positive reinforcement, just as positive punishment is the antithesis of negative reinforcement.

Punishment is a part of life, whether you are a dog, or a person, or some other creature. Punishment is the only way to make a behavior less likely to recur. Even with something as simple as training your dog to sit, punishment is required. If Fido sits, you say “good boy,” click a clicker (maybe), and offer some food. If Fido does not sit, you withhold the treat as a consequence. That is negative punishment. Anyone who tells you otherwise is either misinformed regarding behavioral science or is lying to you. What we do when we are training our dogs is to provide reinforcement or punishment in response to our dogs’ choices, to make them more or less likely to happen again. We do this by giving them something or taking something away. We only get to decide what things we give and take, and for which behaviors we do so.

When dealing with dogs, we always use praise (in the form of treats, verbal praise, or petting) for the application of positive reinforcement and the withholding of these as negative punishment. For dogs in the 21st century, remote e-collars are the clear choice for the application of positive punishment and negative reinforcement.

Why are these two quadrants necessary, if we can punish by withholding a reward?

It’s necessary to apply an unpleasant external stimulus because the lack of a reward is not always enough to halt unwanted or unsafe behavior. In other words, some activities are self-reinforcing to dogs. Incessant barking, chasing other animals, and scavenging for food scraps (in the form of begging, counter-surfing, and stealing) have huge potential upsides. They are also in line with dogs’ instincts. Keeping the food off of the counter and out of reach of the dog is negative punishment, but it will never make your dog stop looking.

Classical Conditioning

Also known as Pavlovian Conditioning, this is the oldest-known and most basic way for a dog to learn. If you have ever taken a psychology or biology course, you may be familiar with Ivan Pavlov and his dog-related experiments. In these tests, he gradually conditioned dogs to begin salivating at the sound of a bell - not really just a bell, but an arbitrary noise that had no prior meaning to the dogs. He did this using food, a stimulus that naturally makes dogs begin to salivate. By repeatedly giving food immediately following the sound of the bell, those dogs came to associate the sound with feeding time. As such, the dogs would begin to salivate even if the food did not come.

For our purposes, there are a few key points to consider. First, the dogs could not help but salivate at the sound, having been conditioned to expect food. Classical conditioning is an automatic physiological response and requires no effort from the dog. Second, it is possible to extinguish these associations over time. Pavlov went on to teach the dogs to forget the meaning of the bell, by separating its sound from feeding time. With some of his dogs, he rang that bell over and over, without the subsequent feeding. Eventually, those dogs stopped salivating at the sound. So dogs can become habituated to a stimulus and stop reacting to it. Third, this process works for both appetitive (pleasant) stimuli and aversive (unpleasant) stimuli.

For the purposes of dog training, we are less interested in classical conditioning, because it does not require the dog to do anything or refrain from doing anything. It does not matter what exactly Pavlov’s dogs were doing when the bell sounded. Whether they were sitting, standing, lying down, pacing around their kennels, barking, or quiet, the bell sounded and they either got food or they did not. Mostly, you will find that classical conditioning helps explain why our dogs do certain things, like barking at doorbells, and how we can use it to break that cycle.

What Is “Science-Based” Dog Training?

There’s a lot of confusion out there about how dogs learn, what we can do to help them, and what the science says about dog training. “Science” is a buzzword that’s often thrown around to add weight to a particular point of view. But real science is based on hypothesis and testing, and conclusions are drawn from the results of those tests. Starting with an end goal in mind and setting up a study to fit your desired conclusion is just propaganda. Or put more bluntly - it’s bullshit.

Anytime you see a trainer marketing their approach as “science-based,” you should consider their motivation for doing so. Animal behavior is indeed a science. But it’s not cutting-edge stuff. Our understanding of animal behavior has remained pretty solid for about a hundred years. Often, it’s a marketing term used to make the trainer appear progressive and evolved. As if they have some special knowledge others don’t. Yes, science is important, but no trainer has any unique claim to it.

In the next couple of posts, I want to cover the well-established and uncontroversial view of animal behavior science. This is the stuff that’s been agreed upon by biologists and psychologists everywhere. You’ll find it in textbooks for both subjects. Specifically, I’m referring to the topics of classical conditioning and operant conditioning. These govern the associations that animals make with their environment, as well as the behaviors they choose to engage in, respectively. Understand them, and your dog’s behavior becomes really easy to understand. Ignore them at your own peril.