MATT’S DOG BLOG

Operant Conditioning

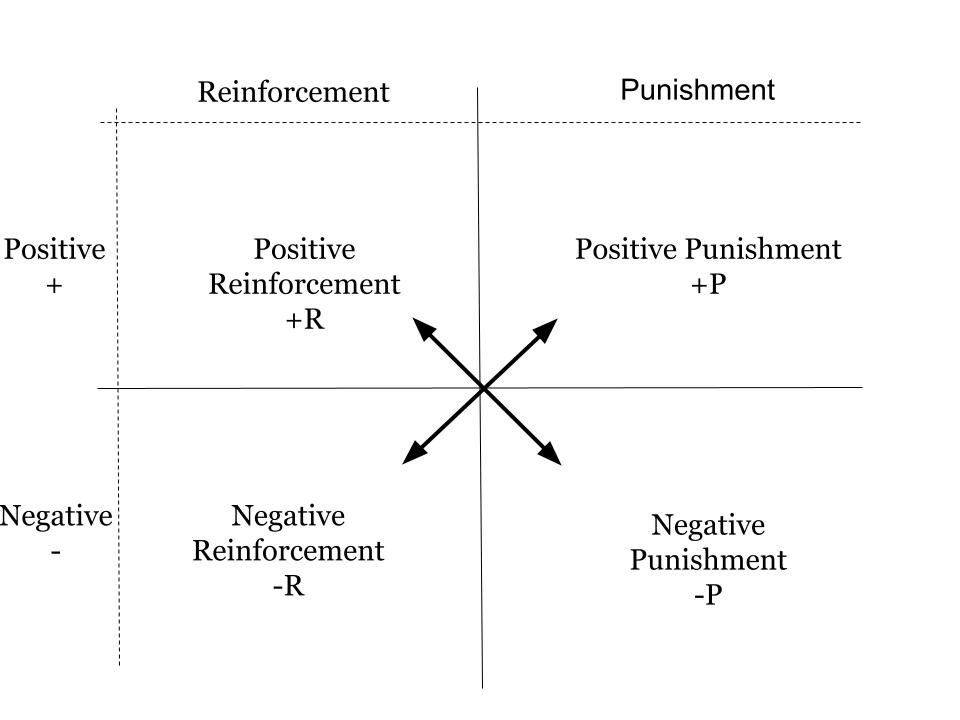

This form of learning requires input from dogs and is the primary way in which we can affect their behavior. Our dogs can generate a response through action or inaction. Operant conditioning consists of four methods of learning, categorized as either positive or negative and either reinforcement or punishment.

The terms positive and negative require some explanation. These terms do not refer to anything good or bad, pleasant or unpleasant. In this context, they are referring to either adding some stimulus or removing it. This giving and taking is the thing that you do in order to influence your dog’s behavior. Reinforcement and punishment are more self-explanatory. Reinforcement involves making the dog more likely to repeat a behavior, while punishment will make the dog less likely to repeat a behavior.

As you can see from the table above, you can give to reinforce or punish behavior. You can also take to reinforce or punish behavior. This concept is confusing for many, and admittedly the differences are sometimes subtle. Below are some examples of how these concepts work, in human terms:

Positive Reinforcement -

Do well on a test and your teacher gives you an A. Show up to work and do your job, you get paid. You are given something (positive) in order to encourage you to repeat (reinforce) a behavior, such as studying or working.

Positive Punishment -

A police officer pulls you over for speeding. Depending on the officer’s mood, your demeanor, and just how fast you were actually going, you may get a ticket. You have been given a fine (positive) in order to reduce the likelihood (punishment) of you speeding in the future.

Negative Reinforcement -

In the years following that speeding ticket or at-fault car accident, your insurance premiums will be higher because you are considered a higher risk to the insurance company. If you behave yourself long enough, those events drop off your record, and your premiums become less expensive. Your insurer lowers your prices (negative) to encourage you to keep driving safely (reinforcement).

Negative Punishment -

If you drive badly enough, the state will take away your license to drive (negative) in order to make you less likely to drive badly (punishment).

You may have noticed I was not able to provide a driving-related example of positive reinforcement. Why do you think that is? Imagine if it were possible for the state to know if you behaved yourself all month, drove the speed limit, stopped fully at every stop sign, and used your turn signal. If you were to receive $100 in your bank account for every month you did these things, would you? What if you got $1,000? $10,000? And what if there were no downside to speeding - no chance of getting caught? Or if you were caught, perhaps the fine was some trivial amount like $5, without the subsequent insurance hike. Would you speed then? Think about how this applies to your dog.

This is how all animals learn and change their behavior. There is no debate about this. It’s a settled issue. These concepts are biological truths, first introduced by Edward Thorndike at the turn of the 20th Century and then refined by B.F. Skinner in the 1930s. All four methods have their place in dog training. Look at these examples long enough, and you will realize there is no way to eliminate punishment from training. Negative punishment is the antithesis of positive reinforcement, just as positive punishment is the antithesis of negative reinforcement.

Punishment is a part of life, whether you are a dog, or a person, or some other creature. Punishment is the only way to make a behavior less likely to recur. Even with something as simple as training your dog to sit, punishment is required. If Fido sits, you say “good boy,” click a clicker (maybe), and offer some food. If Fido does not sit, you withhold the treat as a consequence. That is negative punishment. Anyone who tells you otherwise is either misinformed regarding behavioral science or is lying to you. What we do when we are training our dogs is to provide reinforcement or punishment in response to our dogs’ choices, to make them more or less likely to happen again. We do this by giving them something or taking something away. We only get to decide what things we give and take, and for which behaviors we do so.

When dealing with dogs, we always use praise (in the form of treats, verbal praise, or petting) for the application of positive reinforcement and the withholding of these as negative punishment. For dogs in the 21st century, remote e-collars are the clear choice for the application of positive punishment and negative reinforcement.

Why are these two quadrants necessary, if we can punish by withholding a reward?

It’s necessary to apply an unpleasant external stimulus because the lack of a reward is not always enough to halt unwanted or unsafe behavior. In other words, some activities are self-reinforcing to dogs. Incessant barking, chasing other animals, and scavenging for food scraps (in the form of begging, counter-surfing, and stealing) have huge potential upsides. They are also in line with dogs’ instincts. Keeping the food off of the counter and out of reach of the dog is negative punishment, but it will never make your dog stop looking.

Classical Conditioning

Also known as Pavlovian Conditioning, this is the oldest-known and most basic way for a dog to learn. If you have ever taken a psychology or biology course, you may be familiar with Ivan Pavlov and his dog-related experiments. In these tests, he gradually conditioned dogs to begin salivating at the sound of a bell - not really just a bell, but an arbitrary noise that had no prior meaning to the dogs. He did this using food, a stimulus that naturally makes dogs begin to salivate. By repeatedly giving food immediately following the sound of the bell, those dogs came to associate the sound with feeding time. As such, the dogs would begin to salivate even if the food did not come.

For our purposes, there are a few key points to consider. First, the dogs could not help but salivate at the sound, having been conditioned to expect food. Classical conditioning is an automatic physiological response and requires no effort from the dog. Second, it is possible to extinguish these associations over time. Pavlov went on to teach the dogs to forget the meaning of the bell, by separating its sound from feeding time. With some of his dogs, he rang that bell over and over, without the subsequent feeding. Eventually, those dogs stopped salivating at the sound. So dogs can become habituated to a stimulus and stop reacting to it. Third, this process works for both appetitive (pleasant) stimuli and aversive (unpleasant) stimuli.

For the purposes of dog training, we are less interested in classical conditioning, because it does not require the dog to do anything or refrain from doing anything. It does not matter what exactly Pavlov’s dogs were doing when the bell sounded. Whether they were sitting, standing, lying down, pacing around their kennels, barking, or quiet, the bell sounded and they either got food or they did not. Mostly, you will find that classical conditioning helps explain why our dogs do certain things, like barking at doorbells, and how we can use it to break that cycle.